Rituals and festivals of the ancient Slavs dedicated to the carol. Who is Kolyada? How people were going to carol

Educational material about the Russian folk holiday “Kolyada has come - open the gates”

Kolyada was the name of the ancient Christmas ritual of glorifying the holiday of the Nativity of Christ with songs, as well as the song itself.

IN Ancient Rus' it was my favorite holiday. In Rus', on winter evenings, when it was completely dark, Kolyada walked from house to house - in an inside out fur coat, with an animal mask on her face, with a grip or a stick. “Kolyada was born on the eve of Christmas,” the carolers, the village boys and girls, sang outside the windows. Kolyada will scare children, amuse adults, and go with the crowd to the neighbors. Christmas carolers will still give many performances, but on Christmas Eve they make their first round, as it were.

Once upon a time in Rus', Kolyada was not perceived as a mummer. Kolyada was a deity, and one of the most influential. They called out for the carol and called out, as they did in relation to the lesser deities - Tausen and Pluga. The days before the New Year were dedicated to Kolyada, and games were organized in her honor, which were subsequently held at Christmastide.

The last patriarchal ban on the worship of Kolyada was issued on December 24, 1684. It is believed that Kolyada was recognized by the Slavs as the deity of fun, which is why he was called upon and called upon by merry bands of youth during New Year’s festivities. By the way, when over the course of many centuries the divine meaning of Kolyada disappeared from people's memory, this word began to be used not only for the Christmas performer - the mummer, but in some places (for example, in the Tambov region) for a garden scarecrow, and "carolers" were used to scold the poor. This was the end of the pagan idol.

In Siberia, in the Yenisei region, carolers sang “Vinogradye” at Christmas. A choir of teenagers, and sometimes adults, “timid”, set off with a star in their hands under the windows of the huts. First, permission was sought from the owners to sing “Vinogradye.” If allowed, the crowd entered the hut with words of gratitude:

Like a master in the house, like a master in paradise;

Like a mistress in the house, like a bee in honey,

The children in the house are small, like pancakes in honey...

If the carolers were not allowed in, they would pick up something completely different: “The master is in the house, like the devil is in hell,” etc. Usually, in each hut, the carolers found cordiality and hospitality. After addressing the householders and their children, the singer and choir sang “Vinogradye.”

The star carried by the carolers depicted a stormy sea, a ship and heroes on it. The middle of the star was made from a sieve box, into which a drawing of a ship and a candle were inserted; the outside of the box was covered with oiled paper and the corners with fringe. The star was placed on the handle.

On the second day after Christmas, Christmas fun and entertainment began. Masks were made with great ingenuity, which until the 16th century. called mugs and mugs. For masquerades they dressed up as bears, goats, blind lazars, fighters, old women and even chickens - the sleeves of a fur coat turned inside out were pulled over the legs, the hooks were fastened on the back, a mask with a comb was put on the half-bent head, and a tail was tied at the back. Many jokers smeared soot on their cheeks or rubbed them with bricks, skillfully attached mustaches, and pulled shaggy hats over their heads.

On New Year's Eve, the mummers drove a "filly": two guys were tied back to back, the front one held a pitchfork with a horse's straw head on it. The “filly” was covered with a blanket on top, on which the boy rider sat. The image of a horse, of course, was very dear to the peasant farmer.

On New Year's Eve in the old Russian village they “clicked for oats.” Carolers, and in other places shepherds, went from house to house to scatter grain from their sleeves for fertility. If they were greeted warmly, the callers sang a song in which they promised the owner thick, supper rye, from which “he would get a pie from an octopus ear, from a grain of corn, from a half-grain.” The owners thanked the carolers with “kozulki”—shaped cookies and pies. “Whoever doesn’t give a pie, we will take the cow by the horns,” the jokers said.

For ethnographers, the origin of the word “oat” has long been mysterious. Some researchers folk life They claimed that this word comes from oats, which were sprinkled and sifted on New Year's Eve; other “oats” were traced to the pagan deity Avsen or Tausen. And only to the linguist A.A. Potebne in the 80s. In the 19th century, it was possible to prove that the word “autumn” is connected with the ancient name of January - prosinets, otherwise with the word “to clarify.” After gloomy, early evening days it becomes lighter. This once again confirmed that New Year’s rituals are primarily of agrarian-solar origin.

But here comes the generous New Year, or, as they once said, Vasiliev’s evening. At this time, peasant families sat down to disassemble the pig's head. According to folk symbolism, the pig represents fertility and well-being. So that prosperity would accompany the house throughout the year, they sat down to “break the boar”: the head of the family divided the boiled head into parts, distributing the pieces according to seniority. The smallest of the children crawled under the table to imitate the grunting of a pig. The hostess threw the bones from the table into the pig's cubby: let the pigs not be transferred. Then the family began to eat porridge made from various field grains and peas. Before putting the porridge out of the pot and flavoring it with hemp oil and honey, observant housewives looked closely at how it looked in the pot: if the porridge is ruddy and smoky, the coming year will be successful

During the day at Christmas time, sleigh rides were organized. Arc after arc of fifty sleighs lined up as a train. In Siberia, trotting races were in use: pacers and trotters raced like a whirlwind to the whooping of daredevils.

On Christmastide, weddings were celebrated everywhere in Rus'. It was believed that the time right up to Maslenitsa was the best for this purpose. Many brides waited for matchmakers on Christmastide, which is why January was sometimes even called “wedding season” in official ancient documents. So they wrote: “From weddings to Palm Week,” or: “I came about weddings.”

In the post-New Year's period of Christmastide, on the so-called terrible evenings, grain barns, houses and livestock were protected from the tricks of evil spirits.

On Epiphany, fortune telling was performed for the last time. Various methods of predicting fate include throwing shoes over the gate: “Where the sock points, you will be married in that direction.”

In pre-revolutionary Russia, people did not sleep on Christmas Eve: they went from house to house, treated themselves, caroled, that is, sang carols - ancient Christmas and New Year ritual songs. These days there was nationwide joy. Even kings went to their subjects to congratulate and sing carols. The festive procession usually walked with a paper star and a nativity scene - a brightly painted box in two tiers. With the help of wooden figurines, scenes related to the Nativity of Christ were acted out - the flight to Egypt, the appearance of angels, the worship of the Magi. The death of King Herod was represented in the upper tier, and dancing in the lower tier.

Children, young boys and girls began caroling. They sang carols under the windows of the huts and received various treats for this.

In Rus', the church condemned Yuletide games, fortune telling, and mummers (“masking and putting on animal-like mugs”), and the decree of Patriarch Joachim of 1684, prohibiting Yuletide tomfoolery, states that they lead a person into “soul-destructive sin.” But it was never possible to completely ban the custom of mummers.

They also dressed up (dressed up) in different ways. In noble houses they dressed up as mermaids, Turks, knights, monks, young ladies as hussars, and young men, on the contrary, as ladies. In the villages it was simpler - as a rule, boys caroled as mummers, put on sheepskin coats and masks turned upside down, and depicted various animals - bears, rams, goats, etc.

Common carols were comic choruses where girls sang:

A carol was born

Christmas Eve

Behind the river behind the fast...

And the guys sang along:

To the queen's treasury of gold

The century was full,

So that big rivers

Glory rushed to the sea.

Small rivers - to the mill.

And we will eat this song with bread,

We eat bread, we give honor to bread.

In many literary works carols are described, but perhaps the most vivid description of the holiday is from N.V. Gogol in “The Night Before Christmas”: “Songs and screams were heard through the streets noisier and noisier. The crowds of jostling people were increased by those who came from neighboring villages. The boys were naughty and crazy to their heart's content. Often, between the carols, some cheerful song was heard, which one of the young Cossacks immediately managed to compose.... The small windows rose, and the withered hand of the old woman, who alone, together with the sedate fathers, remained in the huts, stuck out of the window with sausage or a piece of pie. Boys and girls vied with each other to set up their bags and catch their prey. In one place, the lads, having entered from all sides, surrounded a crowd of girls: noise, screaming, one threw a lump of snow, another snatched a bag with all sorts of things. In another place, the girls caught a boy, put their foot on him, and he flew headlong along with the bag to the ground. It seemed like they were ready to have fun all night long..."

Kolyada is a god especially revered by the ancient Slavs. In the last few hundred years, his name has been mentioned only in carols - songs of praise that bring happiness to the house. Learn about the ancient traditions of the holiday in honor of Kolyada, as well as the sacred meaning of carols.

In the article:

Kolyada - god of the Slavic calendar

Not everyone now knows that Kolyada is a god revered by the ancient Slavs. Some even consider it to be the personification of an ancient winter holiday, which will be discussed a little lower, and do not even think about where its name came from. However, even in those times when our ancestors revered the pagan gods, and this was not a violation of the law, Kolyada was mentioned exclusively in carols. Only in one chronicle, dating from the seventeenth century, is he mentioned in the role of a deity.

The Slavic god Kolyada gave people a calendar, the etymology of this word is simple - Kolyada's Gift. In addition, he is considered the giver of the Wise Vedas. Kolyada is also considered the patron saint of farmers and people, born in. Before the calendar, the ancient Slavs used the Chislobog circle, which had 360 days.

Kolyada not only gave a convenient system for calculating years, months and days. He was also a god who sowed peace between neighboring nations. Legends say that the peoples following Kolyada always lived in complete harmony. Therefore, he was revered not only during the calendar period dedicated to him, but also after battles and negotiations between warring tribes. They were grateful to the same god for moving to the western lands.

The Cossacks even considered him their ancestor. Kolyada enjoyed special honor among the kharacterniki. According to Cossack legends, he gave the Cossacks some of his skills and mastery. Every Cossack knew where Cossack strength came from and why they needed a special blessing, but now this knowledge is considered lost. There are practically no characters left.

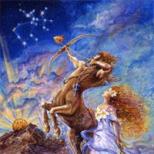

Kolyada was considered one of the sons of Dazhdbog, as well as his smallest personification, the Newborn Sun, depicted as a baby. Kolyada is a young deity. It symbolizes the young sun, which replaces the old one, tired from a year of work in the sky, shining during the holiday dedicated to this deity.

Kolyada is a holiday among the Slavs

So, where did the Kolyada holiday come from? It is dedicated to the god of the same name, who was identified with the young sun, replacing the old one during the winter solstice. After it, the sun gains strength, and the annual circle turns to spring. The daylight remains in the sky longer, and the nights become shorter.

So, where did the Kolyada holiday come from? It is dedicated to the god of the same name, who was identified with the young sun, replacing the old one during the winter solstice. After it, the sun gains strength, and the annual circle turns to spring. The daylight remains in the sky longer, and the nights become shorter.

The Kolyada holiday itself falls on a day when the sun is practically invisible and the heat is impossible to notice. On this day, the night is the longest of the year, and the day is the shortest. However, it was customary to celebrate it for more than one day. Now the equivalent is considered to be the period Christmastide, which last from Christmas to Epiphany.

The birth of Kolyada, the young sun, is identified with the birth of Jesus Christ. Many ancient pagan traditions were converted into a Christian way with the arrival of a new religion in the Slavic lands. Churches were built on the sites of the temples, and pagan holidays replaced Christian ones. However, Christmas, as you know, does not coincide with the winter solstice, which is celebrated on December 21-22 and is considered the first day of Kolyada. The connection with Christmas is also noticeable in the name of the traditional ritual dish - sochivo, which is now called kutya. It is believed that the word “Christmas Eve” comes from it.

Now the holiday of Kolyada has been replaced by Christmas, and the winter solstice is celebrated only by people who honor the traditions of their ancestors. In the old days, this was one of the most significant holidays of the year - a new, young sun is born on this day to give light and warmth to people throughout the year.

Legends have been preserved about the sacrifice of a goat to the young sun and the subsequent recitation of praises to Kolyada. In the old days they believed that this ritual would help the sun gain strength and bring good harvest in the new year.

How boys and girls celebrated Kolyada - carols, an ancient folk tradition

The celebration of Kolyada in the old days was quite noisy. Things were never done without a large group of young people going from house to house. At the same time, they sang and read carols - special texts that had sacred power. A mandatory attribute was the sun, and with the advent of Christianity, a star on a pole, which symbolized the birth of Christ. The procession beat buckets with sticks, banged spoons and other household utensils, people shouted loudly, imitating the voices of animals. Sometimes caroling turned into a real theatrical performance.

The celebration of Kolyada in the old days was quite noisy. Things were never done without a large group of young people going from house to house. At the same time, they sang and read carols - special texts that had sacred power. A mandatory attribute was the sun, and with the advent of Christianity, a star on a pole, which symbolized the birth of Christ. The procession beat buckets with sticks, banged spoons and other household utensils, people shouted loudly, imitating the voices of animals. Sometimes caroling turned into a real theatrical performance.

The older generation organized feasts at this time. Nowadays, having replaced Kolyada, Christmas is considered a family holiday for many people. This was the case before, but in the village all relatives live nearby, and neighbors were often considered close enough people to invite them to the table for Kolyada. It was considered normal to visit several houses and have time to receive guests during the festive evening.

Gifts and treats were always given for carols. Those who do not give anything as a reward for singing winter holiday songs and poems will face, if not ruin, then serious problems with money - as punishment for greed.

Young people went from house to house as mummers, mostly in costumes of wild animals - the skins of, if not bears, then cows were available to everyone. Dressing up symbolized fertility, an appeal to the animal essence of man. With the advent of Christianity, it became generally accepted that mummers drove away in this way evil spirits away from the village. The noise created by carolers has the same meaning.

Nowadays, carolers often evoke exclusively negative emotions. In the old days, the arrival of a festive procession at home was an omen of happiness, prosperity, and a bountiful harvest in the new year. People believed that carols sung by strangers at home had undeniable power. They exchanged food for the prosperity that carolers brought to their homes. In the Voronezh region, it was customary to sit the youngest of the carolers on the threshold and force them to cluck - so that the chickens would lay eggs better all year long.

The treat was often baked goods in the form of animal figures - this symbolized fertility, a good harvest, the health of domestic animals and prosperity. For a long time livestock was one of the main sources of income, so the figures depicting them were also a symbol of wealth. Loaves were also a frequent treat for the Kolyada holiday; they symbolized the obesity of cows. Treats were thrown into a bag that was entrusted to mekhonosh- the person responsible for dividing the spoils between the carolers. Sometimes they also gave money; after the advent of Christianity, it became customary to take it to church after Christmastide.

The treat was often baked goods in the form of animal figures - this symbolized fertility, a good harvest, the health of domestic animals and prosperity. For a long time livestock was one of the main sources of income, so the figures depicting them were also a symbol of wealth. Loaves were also a frequent treat for the Kolyada holiday; they symbolized the obesity of cows. Treats were thrown into a bag that was entrusted to mekhonosh- the person responsible for dividing the spoils between the carolers. Sometimes they also gave money; after the advent of Christianity, it became customary to take it to church after Christmastide.

Texts of carols - “Kolyada came on the eve of Christmas” and others

If you pay attention to the texts of carols, you can learn a lot about the traditions of our ancestors. Many texts have reached our time, but most of them were invented already in Christian times. Thus, most of the carols contain wishes for wealth, harvest and a good life in general for the owners of the house, as well as a request for treats:

The carol has arrived

On the eve of Christmas.

Give me the cow

I'm oiling the head!

And God forbid that

Who's in this house?

The rye is thick for him,

Rye is ugly!

He gets octopus from the ear,

From grain - a carpet for him,

Half-grain pie!

The Lord would grant you

And we live and be,

And wealth

And God create for you

Even better than that!

Some carols contain calls to do what girls have been doing for a long time - fortune-telling on a ridge. They encourage girls to celebrate, and with such carols they often invited representatives of the fair sex who were late to the annual entertainment:

Girls, carols!

Darlings, carols!

Yes, throw combs

For the beds,

Yes, throw combs

For the beds!

Girls, carols!

Darlings, carols!

Yes, bake pancakes

Okay,

Yes, bake pancakes

Okay!

The matter was never limited to one carol, and there were different wishes for everyone who was in the house. As a rule, they wished the owner a harvest, wealth and other benefits, the hostess - family happiness; if there were young girls in the house, they wanted to get married quickly. Despite the fact that the majority considered the procession of carolers to be welcome guests, there were also misers who stinted on the treats or gave too little.

Kolyada is a holiday of the Slavs, the date on which Christmastide began (December 25 - the day of the winter solstice), and they continued until January 6. Thus, even before the adoption of Christianity, people performed Kolyada rituals praising the god of heaven - Dazhdbog. On what date was the holiday Kolyada celebrated after the adoption of Christianity? Pagan celebrations merged with the birthday of Jesus Christ, and Christmastide was already celebrated from December 6 to 19, that is, from Christmas to Epiphany. These Christmas traditions continue to this day.

Kolyada is a diminutive of “kolo”, the sun-baby (it was represented as a boy or a girl, because for a small child, gender does not yet play any role; the sun itself is neuter).

This deity arose from the holiday of the winter solstice, from the poetic idea of the birth of the young sun, that is, the sun of the next year. (This ancient idea of the annual baby has not died to this day. It has been transferred to the concept of “new year”. On postcards and in New Year’s decorations for festivities, it is no coincidence that artists depict the new year in the form of a boy flying in space).

(Kaleda, Kolodiy (Serb.), Calenda (lat.), Kalenda, Kadm (Persian)) - God Kolyada - God who gave the Clans who moved to the western lands: the Calendar (Kolyada's gift) and his Wise Vedas. Patron God of farmers and the Raven's Hall in the Svarozh Circle. “Sixth Kolyada, it’s a terrible holiday in December...” ( "About Vladimirov's idols" PPY) Kolo is the oldest name for the sun, circle (Kol is also one of the popular names for the polar star) and Kolyada means round. From the kolo-circle came such words as wheel, kolach, kolobok.

Kolyada is the ancient god As, who personifies the revival of the winter sun and nature; in Persia (Perun’s radiance) he was revered under the name Mithra (Mini - minimal, t- that, Ra - radiance).

Carols are celebrated from the day of the winter solstice, when the day “at the sparrow’s leap” has arrived and begins to flare up Winter sun, and until the day of Veles. And since, according to some sources, it was believed that Kolyada was the son of Dazhdbog, the holiday of Kolyada was also called Dazhdbog’s day (at this time there was also the longest night, so it was called Karachun’s night, i.e. shortened). It was a day of feasts, food, fun, sacrifices:

“Kolyada was born on Christmas Eve. Behind the steep mountain and behind the fast river there are dense forests, in those forests the fires are burning, the fires are scorching, people are standing around the lights, people are standing caroling: - Oh, Kolyada, Kolyada, you come, Kolyada, on the eve of Christmas! Everyone knows that “caroling”—singing holiday songs and receiving treats and gifts for it—is customary at Christmas. And somehow it is generally accepted that carols are associated with the New Year. However, this custom is much more ancient than it seems. Back at the time when New Year The Slavs celebrated in September; in December they celebrated the Christmas of Kolyada - the birth of the young god of light and warmth.

This happened on the current day of the solstice (December 21-25), when the day begins to lengthen, albeit at a sparrow's pace. At the same time, the generous goddess Lada was honored; Isn’t this where another name for carols comes from – “Shchedrovki”? The sign of Kolyada was a wheel with eight spokes painted in bright colors - a sign of the sun, and in the center of the wheel there should be a fire - a bunch of straw, a candle or a torch. Calling on Kolyada to send warmth to the earth as soon as possible, they sprinkled the snow with colored rags and stuck dried flowers, carefully preserved from the summer, into the snowdrifts. On this day, all the fires in the stoves were extinguished for a while and a new fire was lit in them, called Kolyadin fire. Since Kolyada was the god As from the family of the god Svarog, whose usual incarnation in houses was considered a large sheaf, Kolyada was also represented by a sheaf or a straw doll. Kolyada was also revered as the god who gave people a new calendar.

Among the ancient Slavs, on December 25 (the month of Jelly), the sun began to turn toward spring. Our ancestors represented Kolyada (cf. bell-wheel; circle is a solar sign of the sun) as a beautiful baby who was captured by the evil witch Winter. According to legend, she turns him into a wolf cub (compare the synonyms for “wolf” - “fierce” with the Proto-Slavic name for the harshest month of winter: February - fierce). People believed that only when the wolf's (sometimes other animals) skin was removed from him and burned in the fire ( spring warmth), Kolyada will appear in all the splendor of its beauty.

Kolyada was celebrated on the so-called winter Christmastide (Nomad, Christmas Eve). This same time used to coincide with severe frosts (cf. Moro - “death”), blizzards (cf. Viy) and the most frantic dens of the unclean. This evening everything is covered with a frosty veil and seems dead.

And yet, winter Christmastide is the most joyful of the Slavic festivals. On this day, according to legend, the sun dresses up in a sundress and kokoshnik and rides “on a painted cart on a black tip” to warm countries (for spring and summer).

Later, the holiday of Kolyada was replaced by the holiday of the Nativity of Christ. However, among the Slavic peoples, Christmas is still combined with Kolyada. And everyone Eastern Slavs Caroling has been preserved as a complex of Christmas rituals. Almost all of these rituals came to us from ancient times, when carolers acted as the spirits of ancestors, visiting their descendants and bringing the guarantee of a fruitful year, prosperity, and well-being.

Having put on masks, the mummers went home to carol. The favorite entertainment of young people on Christmas Eve on the eve of Christmas (in the evening of January 6) was caroling, beautifully described in the work of N.V. Gogol.

Guys and girls walked around the village and sang carols under the windows - short ritual songs in which they wished well-being to the owners, and they, in payment for the wish, presented them with delicious food. The more plentiful the treat, the more satisfying the next year should be.

Here is one of the carols that is sung under the windows:

To your new summer,

Have a great summer!

Where does the horse's tail go?

It's full of bushes there.

Where does the goat go with its horn?

There's a stack of hay there.

How many aspens,

So many pigs for you;

How many Christmas trees

So many cows;

How many candles

So many sheep

But they also promised terrible punishments if they did not give gifts to the carolers:

Kolyada, Kolyada,

Who won't give me the pie?

We take the cow by the horns

Who won't give donuts,

We hit him in the face,

Who won't give a penny?

That's neck on the side

After singing these songs, the carolers receive a few money, or more pies, sweets, fruits made from wheat dough; and in other places young carol-players are given a bucket or more of beer, which they pour into a barrel they carry with them.

The most common gifts for carolers everywhere were flour products: special ritual cookies in the form of horses, cows and birds (“kaledushki” in the Moscow province, “ovsenki” in the Ryazan province; “kozuli” - in many areas), round unleavened flatbreads (Saratov “ Kolyadashki", Vladimir "Koledki") and pancakes, butter "kokurki" and "karakulki" in the Novgorod and Vladimir provinces, as well as cheesecakes and pies - everywhere among the Russians. In addition to baked goods, linemen were presented with grain, cereals, flour, butter, sour cream, eggs, beer, tea, sugar, and money.

There were not many other calendar holidays until spring, but the fun in the villages did not die down, because winter is the time for weddings. And those girls who did not yet have grooms organized gatherings - they gathered at some old woman’s place, brought spinning wheels, embroidery, sewing, spent long winter evenings doing needlework, so as not to be bored, sang songs, told fairy tales, sometimes prepared a treat and invited visiting guys.

There are countless ways of fortune telling. This custom comes from the desire to communicate with the ancient Slavic goddess, who was represented as a beautiful spinning girl spinning the thread of fate, the thread of life - Srecha (Meeting) - in order to find out her destiny. For different tribes, the synonyms “court”, “fate”, “share”, “fate”, “lot”, “kosh”, “sentence”, “decision”, “choice” have the same meaning.

On the day of the winter solstice (December 25), it was necessary to help the sun gain strength - so the peasants lit fires and rolled burning ears of corn, symbolizing the luminary. To prevent the winter from being too harsh, they sculpted a snow woman to represent winter and smashed it with snowballs.

In Slavic fairy tales there are many magical characters - sometimes terrible and formidable, sometimes mysterious and incomprehensible, sometimes kind and ready to help. Modern people they seem like a bizarre fiction, but in the old days in Rus' they firmly believed that Baba Yaga’s hut stood deep in the forest, that a snake abducting beauties lived in the harsh stone mountains, they believed that a girl could marry a bear, and a horse could speak with a human voice.

And now the church is diligently destroying small remnants of the former Slavic culture, trying to eradicate even fairy-tale heroes. In particular, not so long ago in Russia, at the insistence of the church, the very interesting Baba Yaga Museum was closed. The Church strongly disapproves of New Year's Father Frost and the Snow Maiden, but so far it cannot do anything about this folk tradition

“Kolyada was born on Christmas Eve. Behind the steep mountain and behind the fast river there are dense forests, in those forests the fires are burning, the fires are scorching, people are standing around the lights, people are standing caroling: “Oh, Kolyada, Kolyada, you come, Kolyada, on the eve of Christmas!”

Everyone knows that “caroling” - singing holiday songs, receiving treats and gifts for this, is customary at Christmas.

However, this custom is much more ancient than it seems. Even at the time when the Slavs celebrated the New Year in September, in December they celebrated the Christmas of Kolyada - the birth of the young god of light and warmth.

This happened on the day of the solstice (December 21-25), when the day begins to lengthen, albeit at a sparrow's pace. At the same time, the generous goddess Lada was honored; Isn’t this where another name for carols comes from – “Shchedrovki”?

The sign of Kolyada was a wheel with eight spokes painted in bright colors - a sign of the sun, and in the center of the wheel there should be a fire - a bunch of straw, a candle or a torch.

Calling on Kolyada to send warmth to the earth as soon as possible, they sprinkled the snow with colored rags and stuck dried flowers, carefully preserved from the summer, into the snowdrifts. On this day, all the fires in the stoves were extinguished for a while and a new fire was lit in them, called Kolyadin fire. Since Kolyada was the god As from the family of the god Svarog, whose usual incarnation in houses was considered a large sheaf, Kolyada was also represented by a sheaf or a straw doll.

……The meaning of the word Kolyada different nations different: For some, Koleda is revered as the deity of festivals and some church rituals are also called, and koledowati (kolodovati) means the walking of children to different houses with songs and dances.

Among the Czechs, Bulgarians and Serbs, Kolėda, as well as wanoenj pиsnеky, means a Christmas song, chodиti po Kolėde, (to walk along the kolėde) means to congratulate you on the New Year and for this to receive gifts from everyone who can give something.

Koleda among the Slovaks means the Blessing of houses, which they have around the feast of the Three Kings, and koledowat - to bless houses.....

Bosniaks, Croats and other Slavic peoples by Koledoya mean a gift for the New Year... . Finally, from the word caroling came the word “witchcraft.” Kolyada, in southern and western Rus', actually on the eve of the Nativity of Christ, which is known in the northeast of Russia under the name Avsenya or Tausenya, and among the Lithuanians it is known as the evening of blocks, or Blokkov, in which almost everywhere in the Slavic world and in Russia porridge is prepared from grain bread and from millet and kutia fruits, reminiscent of the Indian Perun-Tsongol and Ugady, during which the lot in the coming year was guessed by boiling millet...

In the 19th century, near Moscow, it was a custom to call Christmas Eve “Koleda” and on Christmas night to carry a girl in a sleigh, dressed in a shirt over all her warm clothes, which was passed off as Koleda; We don’t know whether such a custom still exists today.

There is an assumption that both the celebration of Koleda and her name moved from Novgorod to Kostroma and other Great Russian provinces in the 15th centuries

After the carols, the evening meal began. At this time, the Nativity Fast ended. Traditionally, Christmas Eve kutia (a dish made from millet and barley) was prepared for the table. Also a mandatory attribute of the Christmas table were figurines of cows, sheep and other animals made from wheat dough. The figurines were given to each other and used to decorate the interior of the house.

The name of Kolyada to this day is constantly heard in carols that contain ancient magic spells: wishes for the well-being of the home and family, demands for gifts from the owners - otherwise ruin was predicted for the stingy. Sometimes the gifts themselves: cookies, loaves of bread were called Kolyada.

Pagan carol festivals have been well preserved and have taken root in our time.

Kolyada is an ancient holiday, a natural holiday bequeathed to us by our ancestors.

And today, when the Russian people want to know their roots, we remember these traditions, these stories, these northern tales of our ancient land!

Carols are a very ancient pagan holiday that was not at all connected with the Nativity of Christ. It so happened that with the advent of Christianity to the Slavic lands, which occurred in the early Middle Ages, the church began to actively fight the old religion. Christian churches were built on the sites of pagan temples, and pagan holidays were replaced by Christian ones. About the same thing happened with Kolyada. During the winter solstice - and this is the main “reason” for the celebration - the birth of Jesus Christ falls. Therefore, it is not surprising that Kolyady is associated with Christmas and has adopted many Christian traditions.

Many even of those who have heard about carols do not know what the word “Kolyada” means. Kolyada - from the diminutive “kolo”, meaning the baby sun. It was imagined as a boy or a girl, because for a small child gender does not play any role, especially since the sun itself is neuter. This deity arose from the holiday of the winter solstice, or more precisely, from the poetic idea of \u200b\u200bthe birth of a small sun. And this newborn sun opens the new year, symbolizes the sun of the next year. It is worth saying that this ancient idea of an annual baby has not died to this day. It is transferred to the concept of “New Year” and on postcards and in New Year’s decorations for festivities, it is no coincidence that artists depict it in the form of a boy flying into space.

Among the ancient Slavs, on December 25 (the month of Jelly), the sun began to turn toward spring. Our ancestors represented Kolyada (cf. bell-wheel; the circle is a solar sign of the sun) as a beautiful baby who was captured by the evil witch Winter. According to legend, she turns him into a wolf cub (compare the synonyms for “wolf” - “fierce” with the Proto-Slavic name for the harshest month of winter: February - fierce). People believed that only when the wolf's skin (and sometimes other animals) was removed from him and burned in the fire (spring warmth) would Kolyada appear in all the splendor of his beauty.

Kolyada was celebrated on the so-called winter Christmastide from December 25 (Nomad, Christmas Eve) to January 6 (Veles Day). This same time used to coincide with severe frosts (cf. Moro - “death”), blizzards (cf. Viy) and the most frantic dens of the unclean. This evening everything is covered with a frosty veil and seems dead.

And yet, winter Christmastide is the most joyful of the Slavic festivals. On this day, according to legend, the sun dresses up in a sundress and kokoshnik and rides “on a painted cart on a black tip” to warm countries (for spring and summer).

Later, the holiday of Kolyada was replaced by the holiday of the Nativity of Christ. However, among the Slavic peoples, Christmas is still combined with Kolyada. And all Eastern Slavs preserved caroling as a complex of Christmas rituals. Almost all of these rituals came to us from ancient times, when carolers acted as the spirits of ancestors, visiting their descendants and bringing a guarantee of a fruitful year, prosperity, and well-being. For the holiday, boys and girls dressed up in hari, or larva, and a scarecrow. The mummers walked around the courtyards, singing carols - songs glorifying Kolyada, which gives blessings to everyone. While caroling, they walked around the courtyards, singing carols, osenki, shchedrovki, grapes with wishes of health and prosperity to the owners, and later also Christmas carols glorifying Christ. At Christmas we went with the children, carried a nativity scene with us, showing performances of gospel stories.

Caroling took place almost the same everywhere.

The diagram below shows the evolution of caroling:

1. Ritual. It represented a sacrifice (goat). After which the mummers performed a sun spell.

2. Pagan rite. This included a ritual meal (kutya, cookies in the form of livestock figurines). Walking around the yards with the “sun”, singing agricultural carols, “feeding Frost”.

Walking around yards with a “star”. Praise of Christ, agricultural carols on St. Basil's Day.

On Christmas Eve, called Christmas Eve, the church charter prescribed strict fasting with complete abstinence from food until the first star. It symbolized the Christmas star, which announced the Nativity of Christ to the Magi. The word “Christmas Eve” itself comes from sochivo, a lean grain porridge made with hemp juice with dried berries or honey (the same as kutia). Sochivo was allowed to be eaten on Christmas Eve as evening approached.

On this day, it was customary to glorify the well-being of home and family (they wanted everything “that the owner likes”). And in order to receive a blessing, it was necessary to please the carolers, which they took advantage of, cheerfully demanding gifts and gifts. This was considered something like a gift for caroling. They playfully predicted ruin for the stingy. At the same time, gifts could be anything, mostly food. Typically, carolers were given ritual cookies, bagels, cows, kozulki, pies and loaves, the so-called symbols of fertility. The loaf, for example, symbolizes the fatness of the cow (old word - krava).

Later, with the advent of Christianity, some not so significant changes were introduced into the celebration of Kolyada. Boys and girls still acted as carolers, sometimes young people took part in caroling married men and married women. To do this, they gathered in a small group and walked around peasant houses. This group was led by a fur-bearer with a large bag.

Carolers walked around the houses of peasants in a certain order, calling themselves “difficult guests”, bringing the owner of the house the good news that Jesus Christ was born. They called on the owner to greet them with dignity and allow them to call Kolyada under the window, those. to sing special benevolent songs, called carols in some places, and ovens and grapes in others.

After singing the songs, they asked the owners for a reward. In rare cases, when the owners refused to listen to the carolers, they reproached them for greed. In general, they took the arrival of the carolers very seriously, gladly accepted all the dignifications and wishes, and tried to give them gifts as generously as possible.

The “difficult guests” put the gifts in a bag and went to the next house. In large villages and villages, five to ten groups of carolers came to each house. Caroling was known throughout Russia, but was distinguished by its local originality.

However, almost everywhere caroling began with the words:

Kolyada, Kolyada!

And sometimes Kolyada

On the eve of Christmas.

Kolyada has arrived

Christmas brought.

Thus, in the central zone of European Russia, as well as in the Volga region, the songs of carolers were addressed to all family members and were accompanied by exclamations of “Osen, Tausen, Usen” or “Kolyada”, which gave the name to the ritual itself - “Click Osen”, “Click Kolyada”. During the rounds, the carolers approached the house, stood under the window and said in a recitative: “Master and mistress, order the oats to be called!”

After permission “Call!” the praise of the court and the glorification of the owners began:

Oh, oat, bye, oat!

That autumn walked on bright evenings,

What was Ivanov's yard looking for?

Ivan has three towers in his yard:

First tower- bright month

Second tower- red sun,

Third tower- often stars.

What a bright month- then Ivan is the owner,

That the sun is red- then his mistress,

What are stars common?- then his children.

After this, wishes for economic well-being were heard:

God forbid him

God bless him.

So that rye is born,

She fell into the threshing floor herself.

From the ear- octopus,

From half grain- pie,

From the ax- lengths

The width of a mitten.

These wishes of the carolers portrayed a vivid and deliberately exaggerated picture of economic well-being and family contentment.

Each peasant family wanted “a hut for the boys, a stable for the calves,” “a son worth four arshins,” “a stable of horses,” “one and a half hundred cows, ninety bulls,” so that “one cow would milk a bucket, one mare would milk a bucket.” I carried two carts." At the end, the carol ended with a request for alms and a threat of punishment for the owners if they refused. The carolers said:

Our autumn

Serve it completely!

Give it, don't break it,

And if you break-

You can’t drive me out of the yard,

But you won't give it to me-

For the New Year, a spruce coffin for you,

Aspen cover,

And remember the mangy mare.

IN different parts In Russia, caroling took place in different ways. For example, in the northern provinces of European Russia, caroling took on a slightly different form. Here carol songs, accompanied by the exclamation “My grapes are red and green!”, were aimed at glorifying each family member living in the house. The carolers began with songs under the window:

Yes grapes, yes red and green!

Yes, we don’t walk around Novo-Gorod,

We are not looking for gentlemen of the yard.

The master's courtyard and high on the mountain,

Yes, high on the mountain, but far to the side,

Seventy miles away

yes on eighty pillars.

The ritual itself ended in the hut with a traditional request for alms:

Isn't it time for you, master, to give and reward?

Not a ruble for you, master, not a half ruble,

At least one gold, sir, hryvnia,

At least a glass of wine

Yes, a glass of beer.

Here is a version of children's caroling. The children, approaching the hut, began to sing:

Give you, Lord,

In the field of nature,

Threshed on the threshing floor,

Kvashni thickening,

There is sporin on the table,

The sour cream is thick,

The cows are milked!

According to tradition, carolers demanded payment and treats very persistently:

...We, the Slavs,

Don't cut half a ruble-

Single hryvnia.

Beer bro

Egg box,

Wine bottle,

A barrel of kvass,

Fish face.

Shaneg dish,

Pancake maker

And butter krynitsa!

As a result, the ritual of caroling consisted of a kind of exchange of gifts, gift for gift. The carolers “gave” prosperity to the peasant house for the whole year, and the owners gave them kozulki, as well as pies, cheesecakes, beer, and money.

It is worth saying that in many areas of Russia, bread products were considered the main gift. On the eve of Christmas, kozulki were baked especially for distribution to carolers. Carol songs have always been varied. And this diversity depended on in which area, even in which region, caroling took place.

And God forbid that

Who's in this house?

Rye is thick for him.

Dinner rye!

He's like an ear of octopus,

There is enough grain for him;

Half-grain pie.

I would give you, gentlemen,

And living and being,

And wealth...

If the owners brought out the treat, the carolers thanked them with the following words:

From a good man

Rye is born good:

A spikelet of thick

The straw is empty!

And here is another version of what they said as a sign of gratitude for the generous gifts from the owners of the hut:

Kolyada-molyada!

You came to the yard

Christmas Eve

On a snowy field.

Walk in the open air!

Ran into the yard

To Ivan Ivanovich,

To Aunt Praskovya.

Ivanov's yard

Overgrown with grapes,

At Ivan's

High tower,

In Praskovyushka's yard

Fully full.

The swan geese were flying!

We are small

Carolers,

We came

glorify,

Honor the owners!

Ivan Ivanovich

Live a hundred years!

Praskovyushka

Always good health!

To all the kids,

Sons-in-law, daughters-in-law,

To the sons and daughters of the boyars!

On this day, the peasants usually said: “If you give me a pie, the yard is full, you have three hundred cows, one and a half hundred bulls.”

So, near Moscow, thanking the owners for the donated cookies - “a cow, smear the head” - carolers promised the house complete well-being and happiness (there was a belief that in a house where a swallow makes a nest, there will be no misfortunes or troubles):

Give me the cow

I'm smearing the head!

You're a swallow

You're a killer whale

Don't weave nests

In an open field

God bless him

You make a nest

In Peter's yard!

God bless him

One and a half hundred cows,

Ninety bulls.

They go to the river-

Everyone is pushing around

And they're coming from the river,-

Everyone is playing.

If the hosts did not serve anything, then the following could be sung for them:

From a stingy guy

Rye is born good:

The spikelet is empty,

It's thick like straw!

To the devils' courtyard; worms to the garden!

Kolyada-molyada,

Kolyada was born!

Who will serve the pie?-

That's the yard of the belly.

More small cattle

You wouldn't know the numbers!

Slavic holidays and rituals

And who won't give a penny?-

Let's close the loopholes.

Who won't give you some cakes?-

Let's block up the windows

Who won't give pie-

Let's take the cow by the horns,

Who won't give bread-

Let's take grandfather away

Who won't give ham-

Then we will split the cast iron!

In some cases, threats against stingy owners could be even worse:

For the New Year

Aspen coffin,

stake and grave

I'll skin the mare!

And yet, as a rule, it did not come to the point of shouting such threats, since the general festive mood and the desire for a good life in the coming year made people generous, tolerant, and hospitable.

The rite of caroling is considered an ancient rite, which was known not only to the Russians, but also to other Slavic peoples. For the ancient Slavs, the arrival of carolers was perceived as a return from another world of deceased ancestors to the homes of their descendants. Therefore, gifting them served as something of a sacrifice in the hope of help and protection in the coming year.

Even with the advent of Christianity, this ritual did not lose its significance. And in the 19th - early 20th centuries, caroling still remained one of the important Christmas rituals, the deep meaning of which, unfortunately, had already been lost. The day after the carol evening, Kolyady themselves celebrated - a holiday that they had been waiting for all year. It was customary to celebrate it within the family circle, but since everyone in the village was brother-in-law, the whole village celebrated.

After a long fast, light food and alcoholic drinks clearly hinted at a long feast, smoothly turning into a cheerful breakfast. From this day on, carolers began to walk - small groups of young people who sang carol songs, glorifying the holy evening, and at the same time the owners. The latter, in turn, tried to present the carolers with various delicacies so that they would not be ashamed either before their neighbors or before the Gods. After all, the ritual of caroling is directly related to the offering of sacrifices to the pagan supreme deities. Thus, in Polesie, the custom has survived to this day of donating money that people give on carol days to the local church.

The carolers were usually accompanied by a goat, but not a real one, but a mischievous and cheerful young man dressed in a casing. The goat was the main character (or face).

The Slavs believed that the presence of this animal in the yard repels evil spirits, brings fertility, a good harvest, joy and prosperity to the house. The ritual of caroling was fun, with laughter, dancing and full glasses, good gifts and a real feeling of celebration. The gifts that young people received for ritual songs and dances went to the common table. Musicians joined in the fun, vodka, moonshine, and cracklings were placed on the table, songs were sung, and round dances were performed. Various games were very popular. The most famous and fully preserved game is the game “Tereshka’s Marriage”. The main action took place at night and always in the largest house. Over the course of several days, or rather nights, the “parents” chose the bride and groom, matched, and got married. All wedding ceremonies were like real ones. Participants in the fun had to be able to dance, dance in circles and sing songs. Preparations for the theatrical game began in the fall, when all the participants were looking forward to these winter carol nights to laugh and dance to their heart's content.